Nine Myths about the Tuskegee Airmen

With the release of the movie “Red Tails” directed by Anthony Hemingway this month, a decades-old debate has resurfaced concerning the combat performance of the pilots of the 332nd Fighter Group (composed of the 99th, 100th, 301st and 302nd Fighter Squadrons) and 477th Bombardment Group, often collectively referred to as the Tuskegee airmen. The movie having mostly received poor reviews, a number of activists have taken to social media to protest against what is thought to be a racially-tinged effort to denigrate the contribution of the wartime fighting unit. Seven decades after the events took place, it is sad to see that most of what is generally known about the Tuskegee airmen is quite distant from historical reality. Several of these distortions or myths have acquired such sensitivity and widespread acceptance that most historians will actively avoid discussing them. Such is not the case of Dr Daniel L. Haulman, Chief of the Organizational Histories Branch of the Air Force Historical Research Agency, who published in October 2011 a 30-page study entitled “Nine Myths about the Tuskegee Airmen”, a shortened version of his book “Eleven Myths about the Tuskegee Airmen”. Using monthly unit histories, mission reports and other archived documents conserved by the Air Force, Haulman challenges nine popular misconceptions about the Tuskegee airmen and tries to bring some facts and perspective back to the story. The myth of inferiority The first misconception regarding the Tuskegee airmen was that they were inferior. The myth was that black pilots could not perform as well in combat as their white counterparts. Shortly after the Tuskegee airmen entered combat, their performance was officially challenged and their removal from the combat zone was suggested by some. The subsequent study by the Air Force showed that although the combat performance of the 332nd FG was not among the best, it was similar to that of several other 15th Air Force fighter groups. As a result of this study, the Tuskegee airmen remained in the combat zone and allowed to continue their mission.

The myth of “Never lost a bomber” This is probably the most widespread myth, claiming that the Tuskegee airmen never lost a bomber to enemy fighters during escort missions. Haulman details his investigation method concerning this claim and provides multiple references to back up his findings. His research concludes that 27 bombers were shot down by enemy fighters while they were under the protection of the Tuskegee airmen. During these same missions, even more bombers were shot down by enemy anti-aircraft fire but these losses are not taken into account as they were unrelated to the Tuskegee airmen's performance as escort fighters. The myth of the deprived ace Another popular misconception that circulated after World War II is that white officers were determined to prevent any black man in the Army Air Forces from becoming an ace, and therefore reduced the aerial victory credit total of Lee Archer from five to less than five to accomplish their aim. Official records show that Lee Archer never claimed more than four aerial victories and received credit for each of these. He never claimed a fifth victory, and consequently this was never taken away or downgraded to half. Another untrue assertion is that black pilots with four victories were sent home to stop them from achieving ace status. Examination of the deployment of the pilots in such a position disproves this as most remained in combat after their fourth victory, making it possible for them to score a fifth victory.

The myth of being first to shoot down German jets Sometimes one hears the claim that the Tuskegee

airmen were the first to shoot down German jets. The myth that the Tuskegee airmen sank a German destroyer The 332nd FG mission report for June 25, 1944 notes that the group sank a German destroyer in the Adriatic Sea near Trieste that day. The pilots on that mission undoubtedly believed they had sunk a German destroyer, but other records cast doubt on whether the ship actually sank and its nature. Research indicates the ship in question was the TA-22, an ex-Italian destroyer converted to a minelayer and used by the Germans. It was not actually sunk in the attack but was so heavily damaged that it never saw further action and no longer posed a threat to Allied operations. Some sources suggest the destroyed ship was the TA-27, but this ship was sunk sixteen days earlier in another location and its destruction cannot be credited to the Tuskegee airmen.

The myth of the “great train robbery” One of the popular stories about the Tuskegee airmen is sometimes nicknamed the “Great Train Robbery.” According to the story, the 332nd FG would not have been able to escort its assigned bombers all the way to Berlin on the March 24, 1945 mission without larger fuel tanks, and members of the 96th Air Service Group, which serviced the airplanes of the 332nd FG, obtained those larger fuel tanks by force from a train the day before the mission. By working all night, the crews had the P-51s equipped with the larger fuel tanks just in time for the escort mission to succeed. Haulman believes this to be highly unlikely, and indicates no evidence of it could be found. During an interview, one of the crew chiefs of the 301st FS indicated he had no recollection of such an event, and that the larger fuel tanks were obtained through the usual logistical channel. Haulman indicates this myth might have found its origins in the fact that the tanks were delivered by train rather than the usual truck delivery.

The myth of superiority Another popular story is that the members of the 332nd FG were so much better at bomber escort than the members of the other six fighter groups, that bombardment groups requested that they be escorted by the 332nd FG. According to this story, white fighter pilots, unlike the black ones, abandoned the bombers they were assigned to escort in order to chase after enemy fighters to increase their aerial victory credit scores for fame and glory. This is a difficult assertion to prove or disprove, being hardly quantifiable by nature. However, no official documents show that the 332nd FG was specifically requested as escort by bomber groups. An examination of the mission tasking method in use at the time also shows that it did not allow for any such requests to be made. One of the few documents that shows how satisfied bomber groups were with their escorts indicates the highest level of escort efficiency in the 15th AF seems to have been achieved before the 332nd FG was engaged in escort missions and was the consequence of strategic and tactical decisions rather than the performance of a specific unit. A post-war study entitled “Policy for Utilization

of Negro Manpower in the Post-War Army“ praised the 332nd

FG for successfully escorting bombers, but also criticized it

for having fewer aerial victory credits than the other groups

because it did not aggressively chase enemy fighters to shoot

them down, but stayed with the bombers it was escorting. The report

also indicates that while the other fighter groups had a kill

ratio exceeding 2:1 (meaning more than two enemy aircraft shot

down for every aircraft lost in combat), the 332nd FG's ratio

was inferior to 1:1 (meaning the 332nd FG lost more aircraft in

combat than it destroyed).

The myth that the Tuskegee airmen were all black Unfortunately, many articles and references to the Tuskegee airmen are so short that they mislead the reader into thinking that all the members of the Tuskegee airmen organizations were black. Haulman indicates that the units composing the Tuskegee airmen eventually became all-black units but did not start as such. The 99th FS was attached to various white fighter groups for over a year before being assigned to the black 332nd FG. Interestingly, “some of the members of the 99th FS resented being assigned to the 332nd FG, because they had become accustomed to serving in white groups, flying alongside white fighter squadrons, and did not relish being placed with the black fighter group simply because they were also black. In a sense, it was a step back toward more segregation.“ Haulman also notes that white members of the organizations were in leadership positions, and that black officers did not command white officers. In addition, some of the white officers who were in command of Tuskegee airmen opposed equal opportunity. For example, Colonel Robert Selway, commander of the 477th BG, attempted to enforce segregated officers’ clubs on the base and had many of the Tuskegee airmen arrested for opposing his policy. Haulman also indicates that “for every white officer who discouraged equal opportunity for the Tuskegee airmen under their command, there were other white officers who sincerely worked for their success” and gives a list of notable such officers.

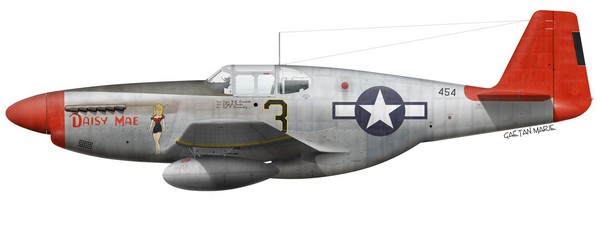

The myth that all Tuskegee airmen were fighter pilots who flew red-tailed P-51s to escort bombers This incorrect perception is the result of decades of simplified depictions of the Tuskegee airmen's history. In reality, the Tuskegee airmen flew four types of fighters in combat, and also the B-25 Mitchell bomber. The Tuskegee airmen made their combat début in North Africa in May 1943 flying P-40 Warhawk, P-39 Airacobra, P-47 Thunderbolt and later P-51Mustang, all with standard camouflage. The red tails only appeared when the group began escorting bomber raids in July 1944.

Haulman finally, and rightly, concludes his paper by stating that “whoever dispenses with the myths that have come to circulate around the Tuskegee airmen in the many decades since World War II emerges with a greater appreciation for what they actually accomplished. If they did not demonstrate that they were far superior to the [other] escort groups of the 15th AF with which they served, they certainly demonstrated that they were not inferior to them, either. Moreover, they began at a line farther back, overcoming many more obstacles on the way to combat. […] Their exemplary performance opened the door for the racial integration of the military services, beginning with the Air Force, and contributed ultimately to the end of racial segregation in the United States.” |

|||||||

|

Advertising

/ Banner Exchange |

|